My Aunt Sevim’s bugged-out eyes and raspy voice were caused by the thyroid condition she came from Turkey to treat. She’d shake me awake on school nights to sneak downstairs for pancakes, cleaning up quietly so we wouldn’t get in trouble.

She once started a indoor water fight with my siblings that flooded the second floor and turned the stairs into a river. She was young at heart…and a little crazy.

Uncle Turgut was my father’s oldest friend. He was a big man with a hearty laugh and a huge hug. He always surprised me by how happy he was to see me.

He lost every business he’d inherited or launched by giving away too much, all the time. Everyone loved him, except his wife.

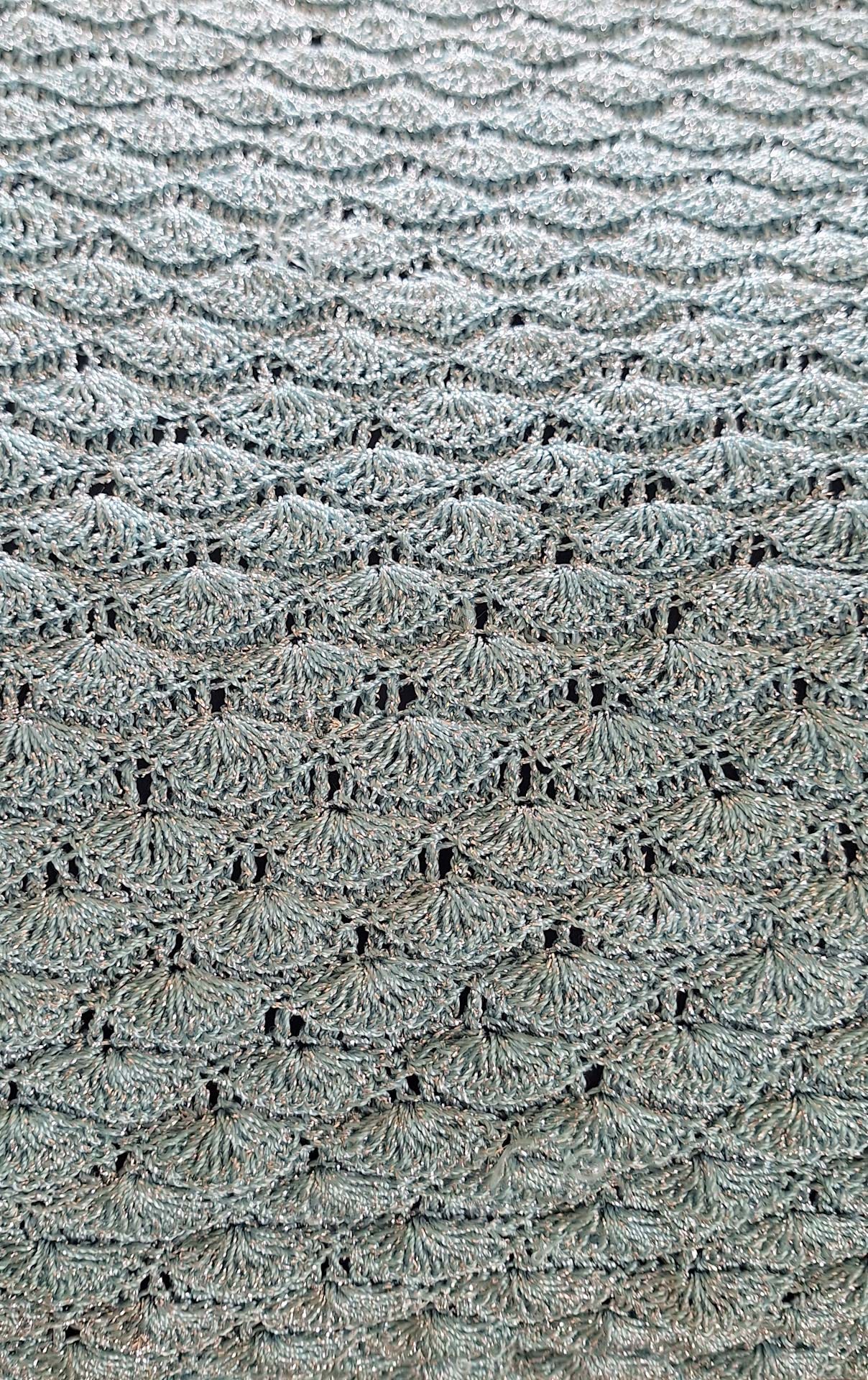

He once dragged a king-sized, crocheted bedspread in first class all the way from Ankara to New Jersey for me. Shapeless in a broken plastic bag, it tried to squirm out of one arm as he lugged his bags down the airport terminal with the other.

It had taken my Turkish grandmother two years to make…but why did she make it?

Maybe because the summer I’d lived with her she had constantly bitched at me for behaving like an American child (which I was) and made me eat home-cooked food that looked like various shades of puke.

Or maybe she wanted to give me a different story to tell when she was gone.

Back in Upstate New York, Sevim’s younger sister, Sevinch, was in charge. It was her house after all. Sevinch took after their mother, learning both that generous nature and her culinary skills from the old hag.

Sevinch’s gift was raising me for 7 years and 3 suicide attempts until I escaped to Iowa to reinvent myself, leaving them all behind. Or so I thought.

Yet here they are, still

Squatting down by the 75th honeyberry bush, a tick crawling up my back and hands cramping, I know I’m doing it wrong, again. For 10 years, I’ve tried to raise these 150 bushes. In 10 years, I’ve grown the equivalent of 10 grocery store trips in berries.

Howard Buffet wrote a book called “40 Chances,” (the title’s the best part) referring to the 40 seasons a farmer gets to learn to farm. I’m going to need to live a lot longer to get this right.

Truth is, I’m no good at it. My pear trees look anemic. The chestnuts scoliotic. And these damned berry bushes. Just when I could be proud that they’d grown into real bushes I learn that all this “bushiness” is keeping them from growing actual fruit! So, this year it’s a scalping and another year’s wait for the fresh stems I now know the berries love.

Why didn’t I know this by now?

Because I’m no better than those fools who claim to have raised me. A gaggle of people from aunts and uncles to the weekend father and disappeared mother all with something - undiagnosed ADD, bipolar disorder, pathological narcissism - turned out some half-assed, rootless, wandering soul, burnt around the edges and dark inside.

We carry our people with us. They’re dead or 1,000 miles or 50 years away and still I hear, still I mimic, their voices judging each other and me.

I carry the slanted weight of every evil I ever overheard lobbed by some adults about other adults in my life. The warped gossip passed off as tasty truth reeked of a smugness that worked its way under my skin like that tick’s going to do before I get to it, leaving a scar even after I get the filthy head out. My body rejects it and tries to heal. Sometimes only antibiotics can help.

Still, I hold it tight because it’s familiar, this judging of everything, of everyone. I chew on it like an old security blanket, gagging when I can’t get enough oxygen. For those of us who carry such people in us, there’s not enough fresh air in a lifetime to clear our lungs of those first few smog-filled years.

Eh, I know I’m not alone. “Everybody’s got something,” as the book says. But really, I am alone, squatting out here pretending I can grow food when I was raised in a place that only grew rocks.

Growing despite them

Mrs. Drake was our elderly neighbor to the south. She lived on the next hill over in an old one-story farmhouse that slanted every which way. It had a mechanic’s winch I always wished was a swing hanging in the big oak out front.

Her son Derry lived with her. He worked on cars for extra money. When he’d come in for a break, his body took up the other end of the kitchen. His red, swollen hands were barely able to pick up his can of beer. “High blood pressure,” they said.

Mrs. Drake and I played Scrabble every day after school during my junior high years, sitting there in her little kitchen, her sink at my back and a giant jade tree thriving in the rotting bay window at my elbow. That plant was four times older than I was. Mrs. Drake was seven times older.

These are what roots looked like, I guess. It was all so unfamiliar and kind.

Mrs. Drake could grow things. She sent me home with flower bulbs, reminding me not to plant them upside down. I suspect I did because they never came up. She tried carrots with me, but they grew into sad yellow squiggles. I soon gave up, as a 12-year-old might without anyone telling her that quitting’s no good a habit to pick up at that age.

I became a jack of all trades and a master of none, just the way they raised me. That’s useful for a lot of things, but by this time in my life, I would’ve liked to have been an expert at something. Anything.

It’s on me, now

I stand up and look over at the terraced orchards. Tree tubes sag on the chestnuts where they melted from an escaped prairie fire 3 years ago. The comfrey around each tree doesn’t keep prairie roots from strangling them like I’d planned. Its annual growth and decay doesn’t feed the soil fast enough to make up for years of abuse it suffered before me.

Pruned honeyberry branches scatter in clusters across the landscape cloth mocking me. ”What took you so long?” “When you gonna learn?”

Uncle Turgut once told me that he spoiled his kids because he wanted them to aspire to the good life. Aunt Sevim taught me how to make joy. Mrs. Drake showed me that putting living things in the ground has its own worth.

Thankfully, I carry them with me too.

I’ve got one more decade in me – if I’m lucky – to do something right. Something that’ll last. Something no one can wreck, rewrite or demean. Especially me.

I just wonder if it’s possible to grow something that strong and healthy in such degraded soil, in so little time.

More scenes from Draco Hill

Sign up for free events all season long. Paid subscribers get perks! Space limited. Learn more.

What a childhood! I never had so many interesting people or adventures in my life.

I stumbled here by way of Jess Piper and I'm glad I did. You are a talented writer. Thanks for sharing.